Asylum From Big Brother

Why I was compelled to flee the United States in 2024

The Backstory

In the summer of 2013 I was an economics student getting ready to transfer to the University of Washington in Seattle. In my spare time, I made some tongue-in-cheek comments about prison reform on a popular economics blog called Marginal Revolution (www.marginalrevolution.com), and the blog’s co-author, George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen of Virginia, responded to them in a jovial fashion.

The trouble started on October 8, 2013, when Cowen posted an article titled “What are the ethics of the cyborg cockroach? (Franz Kafka edition)” referring to a microelectronic kit that controls the movements of cockroaches via Bluetooth signals sent from a smartphone.

To this I commented under the name “Human version,” saying “[t]he Jews are going to love this:” and linking to a story about a helmet that can control human limbs with electrical signals sent to the brain. Roughly ten minutes later, Cowen replied by posting another article titled “Seattle markets in everything?” about a company offering poverty tours that allow people to “see the seedier side of Seattle in a new light and have an experience that you will never forget. Embrace the Experience!,” crediting Mark Thorson for the tip.1

Later that same night, October 8, 2013, I was interrupted masturbating on my laptop: the operating system crashed in an unusual way, and when it rebooted I witnessed someone manipulating song files suggestively. The next day, Cowen began posting blogs at Marginal Revolution related to my daily activities on both my computer and phone. This went on for a week or more and then subsided; when I made another comment on the blog, stories related to my daily activities increased. Reformatting my laptop’s storage drive and reinstalling the operating system had no effect, and I would later notice that Cowen was able to make reference to my whereabouts and appearance even when I didn’t have my devices with me, suggesting that he had access to security cameras throughout Seattle. On several occasions during this time I witnessed someone remotely manipulating files on my laptop.

In the midst of this activity, the blog’s other co-author, Alex Tabarrok, posted an article about the ongoing NSA surveillance scandal, titled “Did Obama Spy on Mitt Romney?” that seems to have foreshadowed what was about to happen (“Did Obama spy on Mitt Romney? As recently as a few weeks ago if anyone had asked me that question I would have consigned them to a right (or left) wing loony bin. Today, the only loonies are those who think the question unreasonable.”).

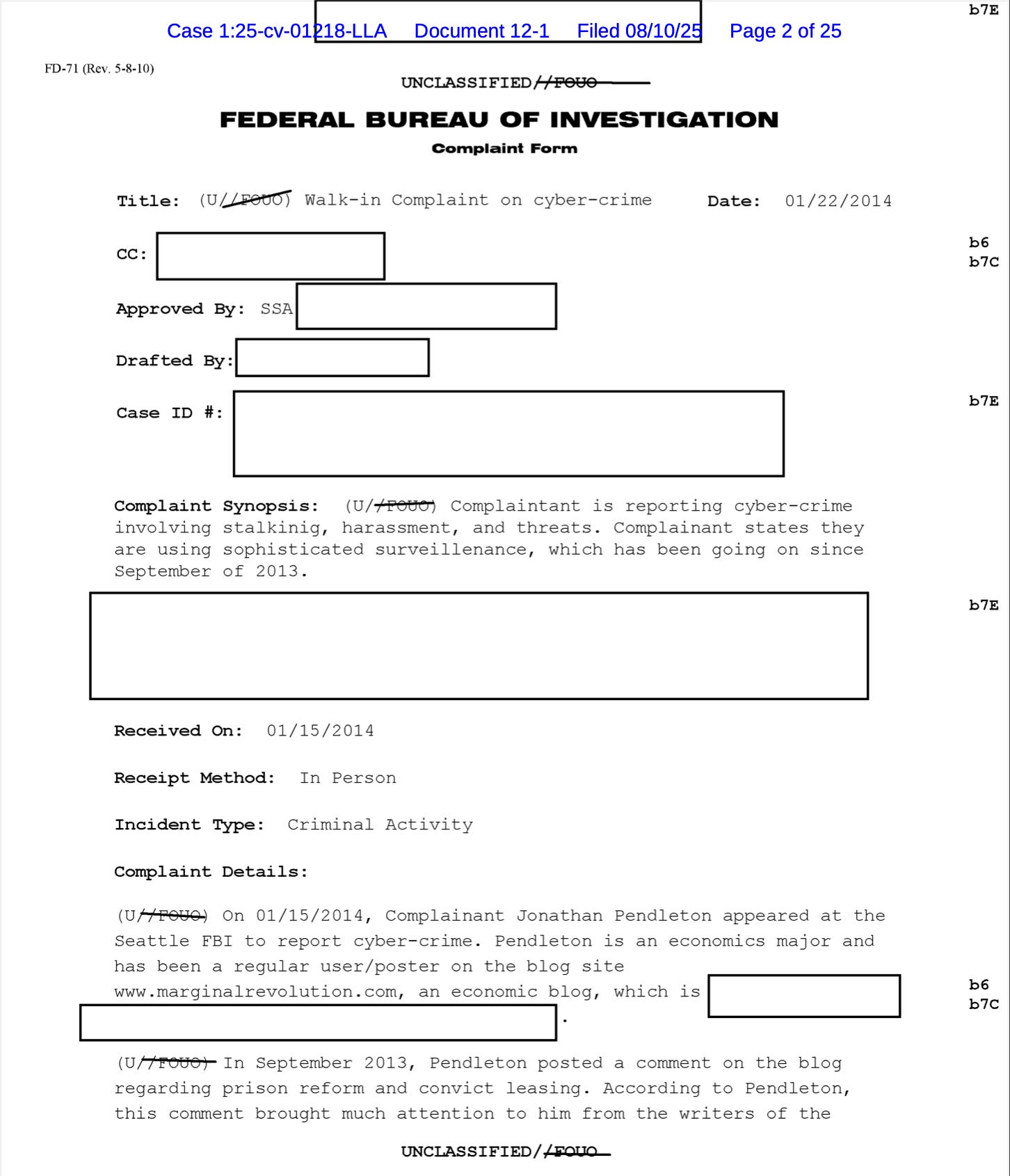

By January 2014, it had become clear that the cyberstalking I was witnessing being perpetrated by Professor Cowen was much more than a prank and needed to be reported to law enforcement, if for no other reason than to get on the record in the event my bank account were to be emptied or lest I end up framed for some cybercrime. I made reports to various police departments and to the FBI field office in Seattle on January 15, 2014.

On January 19, 2014, Tabarrok posted a blog titled “The Chemicals In Our Food,” which is nothing but a picture of a banana followed by a list of chemicals, and around this time I had the first and only manic episode of my life: I woke up early one morning feeling euphoric, as if I were floating, and spent a week or two in a state of intense delirium, visiting museums and bars, making lots of new friends and spending lots of money. It was especially odd because I was lucid enough to recognize that I must have been drugged and that this was a scary situation, but I felt too good to care. Unfortunately, I also made a number of statements during this time that thoroughly discredited me, which was of course the idea.

In February 2014, I decided to take a break from the college semester and embarked on a road trip to get out of Seattle and visit friends and family across the country. Along the way, I stopped in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to visit my ex-girlfriend and noticed that our liaisons were being remarked upon — both on the Marginal Revolution blog and through the manipulation of algorithmically generated content in various newsletters and advertisements. There were indications that she was being monitored. This made me extremely angry and I made further attempts to report this activity to law enforcement with no result.

In March 2014, after doing some research back in Seattle, I announced on the Marginal Revolution blog and to various law enforcement agencies that I would be making a citizen’s arrest of Professor Cowen according to the common law of Virginia:

If the police and FBI won’t arrest you for hacking my computer and sexually harassing me over the past several months, I will do it myself -- in the next couple weeks before school starts again.

The charge was felony violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1030, “gaining unauthorized access to a protected computer” in furtherance of stalking or harassment. See US v. Cioni, 649 F.3d 276 (4th Cir. 2011) (felony enhancement under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act).

Felony citizen’s arrest is lawful in Virginia. Burke v. Com., 515 S.E.2d 111, 30 Va. App. 89 (Ct. App. 1999) (ruffians arrested by a private security guard using pepper spray); Tharp v. Com., 270 S.E.2d 752, 221 Va. 487 (1980) (accused rapist arrested at his home). The requirement is simply that (1) a “felony had actually been committed,” and (2) that there were “reasonable grounds for believing the person arrested had committed the crime.” See Tharp at 754.2

I then flew from Seattle to Virginia and visited the George Mason University police at the Fairfax campus. I explained what had happened on Professor Cowen’s blog and offered to show them the evidence I had gathered. When I did not hear from the police after roughly one week, I located Mr. Cowen in a classroom at GMU’s Arlington campus on March 26, 2014, and announced that I was making a citizen’s arrest. I gave Mr. Cowen a chance to comply and when he started to flee I attempted to subdue him with pepper spray and a stun gun, which seemed to me the safest way to effectuate such an arrest and prevent a potentially violent reaction. Naturally, this caused quite a stir and the incident was written up in several publications, including the Huffington Post (“Tyler Cowen Pepper Sprayed While Teaching Law School Class On Vigilantism”).

Nobody was familiar with the common law of felony citizen’s arrest, and, as expected, I was instead arrested by the Arlington police and charged with misdemeanor assault and battery — though I did not anticipate also being charged with felony “abduction,” and felony “malicious injury by means of a caustic substance,” a legal fiction as applied to pepper spray which carries a mandatory sentence of 5-30 years (pepper spray is not a caustic substance).

On the basis of Cowen’s perjured testimony, I was denied bond and held in jail for nine months before trial. Cowen’s testimony at a hearing on April 29, 2014, as reported in the Washington Post, was this:

“‘I was accused of having controlled [Pendleton’s] mind at a distance and also [of] sexual harassment,’ explaining that the mind control allegedly occurred ‘by computer technology at a distance.’”

See “Tyler Cowen’s Attacker Thought The Professor Was Controlling His Mind, Cowen Testifies.” Washington Post, April 29, 2014.

When it became clear on the third day of trial that my affirmative defense was not being competently presented, I reluctantly agreed to enter a dual pleading of “not guilty” or “not guilty by reason of insanity.” This was the public defender’s idea of a defense strategy; I denied having any mental illness during testimony. Nevertheless, on December 15, 2014, I was acquitted not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) in the Circuit Court of Arlington County, Virginia. My plausible legal defense was never presented.3

Insanity

The Supreme Court definitively outlawed “criminal commitment” on equal protection grounds in Baxstrom v. Herold , 383 U.S. 107, 86 S. Ct. 760, 15 L. Ed. 2d 620 (1966), reasoning that “there is no conceivable basis for distinguishing the commitment of a person who is nearing the end of a penal term from all other civil commitments.” Id. at 112.

In Jackson v. Indiana , 406 U.S. 715, 92 S. Ct. 1845, 32 L. Ed. 2d 435 (1972) the Supreme Court noted that the “Baxstrom principle also has been extended to commitment following an insanity acquittal,” Id. at 724 (citing cases). Naturally, if a prisoner who has been convicted of a crime is entitled to a civil commitment hearing, then someone who has been acquitted of a crime would receive the same protections.

It was not until Foucha v. Louisiana , 504 U.S. 71, 112 S. Ct. 1780, 118 L. Ed. 2d 437 (1992) that the Supreme Court explicitly held what had been logically implied for decades: following an insanity verdict, the state has “no punitive interest” because “[acquittee] was not convicted, he may not be punished,” and “keeping [an insanity acquittee] against his will … is improper absent a determination in civil commitment proceedings of current mental illness and dangerousness.” Id. at 78-80 (emphasis added).

“This, of course, is an equal protection argument (there being no rational distinction between A and B, the State must treat them the same).” Id. at 108 (J. Thomas, dissenting). “It should be apparent from what has been said … that the [State] … discriminates against [the acquittee] in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” Id. at 84-85 (majority opinion).

But as the New York Times Magazine has pointed out, quoting W. Lawrence Fitch, a former director of forensic services for the State of Maryland, “in practice states have ignored Foucha to a pretty substantial degree.” McClelland, Mac. “When ‘Not Guilty’ Is A Life Sentence.” New York Times Magazine, September, 27, 2017.

In February of 2015, following my acquittal in the Circuit Court of Arlington County, I was taken to Central State Hospital (CSH) in Petersburg, Virginia, for “evaluation as to whether the acquittee may be released with or without conditions or requires commitment.” Va. Code § 19.2-182.2.

Upon arrival I was given a brief intake evaluation during which I was asked simple questions about my whereabouts, the reason for my visit to the hospital, and the presence of any violent ideations he might be having. I was asked to name U.S. presidents in reverse order, getting as far as Gerald Ford before being stopped. I was asked to remember three words, which were “apple,” “penny,” and “table.” The doctor, one of the lead forensic psychiatrists at CSH, admitting that I had passed the evaluation, then said, “you may not be ready to hear this but the judge has already decided that you have a mental illness, so you’re going to have to play along.”

During the first few weeks at CSH, I was housed in an intake unit with patients that were foaming at the mouth and yelling, wearing their shirts as underwear. I would stand with his back against the wall to avoid being attacked indiscriminately by raving lunatics. I was eventually attacked early one morning by another patient who thought himself to be the second coming of Christ.

I was told by different doctors that I would be medicated against my will and later that I would “never get out” until I agreed to take medication prescribed for an illness that had barely been diagnosed. Attempts to maintain my innocence and question the varying diagnoses were regarded as a “lack of insight” into a nonexistent mental illness.

All this happened before I was committed. By the time of the initial commitment hearing in May 2015, I had already been coerced into taking olanzapine (Zyprexa) which eventually caused serious health problems, and was telling the doctors whatever they wanted to hear in order to maximize my chances of release.

Nonetheless, I was committed in May of 2015, despite not having any mental illness, a category of error that the Supreme Court has recognized as being significantly more traumatic and stigmatizing than a criminal conviction followed by detention in the general population of a jail or prison, e.g. Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480, 100 S. Ct. 1254, 63 L. Ed. 2d 552 (1980) (grievous loss); United States ex rel. Schuster v. Herold, 410 F.2d 1071 (2d Cir. 1969) (agony); Matthews v. Hardy, 420 F.2d 607 (D.C. Cir. 1969) (severe emotional and psychic harm).

Out of a concern for campus safety, George Mason University had written a letter to the court urging that I should be committed because my release would pose too great a risk to students and faculty.

Though I have still been unable to retrieve the psychiatric evaluations used for my initial commitment, my recollection is that the one evaluator who recommended commitment found that my alleged mental illness was “in remission.” Considering that this was part of a split decision — the other evaluator recommending release, this could hardly be “clear and convincing” evidence of either mental illness or dangerousness.

But the Virginia statute used for NGRI commitments, Va. Code § 19.2-182.3, does not mention the heightened standard of “clear and convincing” evidence — the burden of proof required for civil commitments which tends to be closer to “beyond a reasonable doubt” than a “preponderance of the evidence.” Moreover, § 19.2-182.3 is defective because (1) mental illness and dangerousness are described as “factors” rather than coextensive requirements, (2) it explicitly allows for a finding of mental illness that is “in a state of remission,” and (3) considers only the “likelihood” of dangerousness in the “foreseeable future.”

This language plainly does not describe the due process standard for involuntary commitments after Foucha, and these are the same statutory criteria used to continue confinement under Va. Code § 19.2-182.5, which means that insanity acquittees in Virginia can be hospitalized indefinitely based on a presumed mental illness and the prospect of future dangerousness, with no statutory right of appeal to a jury afforded under the State’s analogous civil commitment statute, Va. Code § 37.2-814(D)(v).

Indeed, Virginia’s NGRI statutes under Va. Code § 19.2-182.2, et seq., differ in every respect from the State’s civil commitment statutes under Va Code § 37.2-808, et seq.. The two statutory schemes are substantively and procedurally unequal at every stage. Based on my experience, I believe Virginia’s NGRI statutes are likely to be found responsible for systematic wrongful commitments throughout the State, including my own.

NGRI commitment orders in Virginia are effectively two-year “criminal insanity” sentences in most cases because, while the State does review confinement after twelve months pursuant to Va. Code § 19.2-182.5, the courts typically give deference to the DBHDS mandated “gradual release process” which takes a minimum of sixteen months to complete after the acquittee spends several months getting to the civil hospital.

By contrast, the analogous civil commitment statute, Va. Code § 37.2-817(C), caps the inpatient review period at 180 days, and is more often measured in 30, 60, or 90 day increments.

In January 2017, when I was released from the hospital, I was seventy pounds heavier and in a state of hibernation, sleeping sixteen hours a day. I had developed irritable bowel syndrome from the olanzapine and the doctors were recommending an additional medication to control my blood sugar.

After I was released from the hospital under supervision in 2017, the evidentiary standard became “[t]he court shall subject a conditionally released acquittee to such orders and conditions it deems will best meet the acquittee’s need for treatment and supervision and best serve the interests of justice and society.” Va. Code § 19.2-182.7. There is no burden on the State to produce evidence of anything.

These post-release statutes are unconstitutionally vague because they fail to “establish standards … sufficient to guard against the arbitrary deprivation of liberty interests,” Chicago v. Morales , 527 U.S. 41, 119 S. Ct. 1849, 144 L. Ed. 2d 67 (1999).

The result was years of detention without evidence, where the onus fell on me to somehow prove a negative — a distinct lack of mental illness, whereas the civil statutes again cap mandatory outpatient treatment at 180 days absent “clear and convincing evidence” of “recent behavior causing, attempting, or threatening harm.” Va. Code § 37.2-817.01.

In March 2019, my first motion for unconditional release pursuant to Va. Code § 19.2-182.11 was denied without any relevant evidence being presented. The NGRI case manager, Kelly Nieman, explained that she would first like to see me find a job after graduating from college. Judge Louise DiMatteo then announced that it “hasn’t been long enough.”

Simply put, having the misfortune of succeeding with an insanity defense in Virginia, and in many other states, is like falling through a trapdoor in the justice system into a place where no one knows the rules, there are effectively no standards, and the State gets to make you do whatever they want, for as long as they want, until they feel like releasing you — precisely what Foucha was intended to prevent.

But the situation is uglier than the statutory defects suggest. Unlike John Hinkley, most insanity acquittees were not arrested for trying to assassinate the President. The insanity defense is used, much like any other defense, because a defendant believes it to be their best defense against typically more mundane felony charges — and often without realizing the vulnerable position they put themselves in if they succeed.

The idea that insanity acquittees are “getting away with murder” and doing “soft time” in a hospital is largely at odds with reality. I am sympathetic to states like Idaho and Kansas who have decided to abolish the defense altogether,4 and to states like Oregon and the federal Insanity Reform Act of 1984 that made it more difficult for the average defendant to put themselves in a position where they can be continuously confined by a state that is determined to punish them, and in hospitals where the surrounding rehabilitation industry has incentives to treat them for an illness that will justify their ongoing detention. See United States v. Freeman, 804 F.2d 1574 (11th Cir. 1986) (upholding heightened burden on defendants).

One of the bitter ironies of my case is the realization that I would have been better off convicted. My sentence would now be served and I would have saved myself from years of incessant gaslighting and coercive medical treatment.

In May 2019, I graduated from Northern Virginia Community College with an Associate of Applied Science in Cybersecurity and began looking for work. It was around this time that I noticed that a non-profit I was interested in working with had received funding from Emergent Ventures, a pet project of Professor Tyler Cowen’s Mercatus Center at GMU, which in turn had received funding from Peter Thiel. A quick search of the Internet revealed that Cowen and Thiel had been well acquainted for many years.

Thiel had been in the news recently as the co-founder of CIA-backed surveillance company Palantir Technologies, which uses “military-grade” technology to, among other things, monitor “subversives,” and whose clients include “the CIA, the FBI, the NSA, the Centre for Disease Control, the Marine Corps, the Air Force, Special Operations Command … and the IRS.” See “Palantir: the ‘special ops’ tech giant that wields as much real-world power as Google.” The Guardian, Jul. 30, 2017. The company has been referred to as “Big Brother.”5

In other words, Cowen has personal ties and business dealings with Thiel, who manages a company that offers exactly the same cyberstalking capabilities I was describing in 2014. In fact, just months after Cowen had denied during his trial testimony knowing anyone involved in computer hacking or gaining access to computers unlawfully, Thiel appeared on Cowen’s talk show.

I kept this news to myself to avoid being sent back to the hospital since I was still subject to conditional release in Arlington and effectively under duress. Even as late as 2020, as I was expecting to be released, and my then psychiatrist, Dr. Sashi Putchakayala, was privately questioning whether I have any mental illness at all, I was still being warned not to challenge the diagnosis until I am clear of the court.

Procedural History

In January 2020, my first job offer as a Software Test Analyst with Alarm.com in Tysons Corner was withdrawn when the employer learned of the 2014 arrest incident. My background check had reported acquittals for “abduction by force” and “malicious injury by acid.”

Realizing that employment discrimination was going to be a persistent problem, I petitioned to change my legal name to stop prospective employers from Googling my mugshots or conducting background pre-screens before offering job interviews. I also filed a petition to expunge the trial records in Arlington but was told the Supreme Court of Virginia had foreclosed this remedy for persons still on NGRI conditional release in Eastlack v. Com., 710 S.E.2d 723, 282 Va. 120 (2011) (“[an insanity acquittee] is not discharged from the constraints imposed upon him by law as a result of his criminal act,” yet another Fourteenth Amendment violation).

I was soon offered another job that would require me to relocate, but the NGRI case manager, Courtney Nobles, then informed me that she was no longer willing to recommend my release and refused to provide any explanation. I had signed a written agreement with the case workers that was supposed to guarantee release by May 2020, but they refused to give me a copy and began writing violation letters to the court when I complained that they had violated the agreement, abandoned case management guidelines, and were withholding favorable evidence from the court.

I petitioned again for release pursuant to Va. Code § 19.2-182.11 and a hearing was held on August 28, 2020, wherein I was threatened with jail for attempting to subpoena witnesses, was accused by Judge Louise DiMatteo — prior to the hearing — of exhibiting “circular thinking” when no one had raised any mental health concerns (for years), and was not allowed to speak or present other evidence I had prepared.

The NGRI case managers, Kelly Nieman and Angelica Torres-Mantilla, took the stand and perjured themselves by misrepresenting the agreement they had signed and their repeated promises of release. There was, again, no relevant evidence presented.

My psychiatrist, Dr. Sashi Putchakayala — the only doctor involved at this point — took the stand and testified that he was unaware of any symptoms during the 18 months he had been treating me, and did not believe that I was a danger to public safety.

This August 28, 2020, hearing concluded with Judge DiMatteo denying release because I had “fixated on things that didn’t happen” and told the social workers to “assign additional mental health treatment.” I then made a formal complaint to Arlington DHS about the behavior of the case workers that went unanswered.

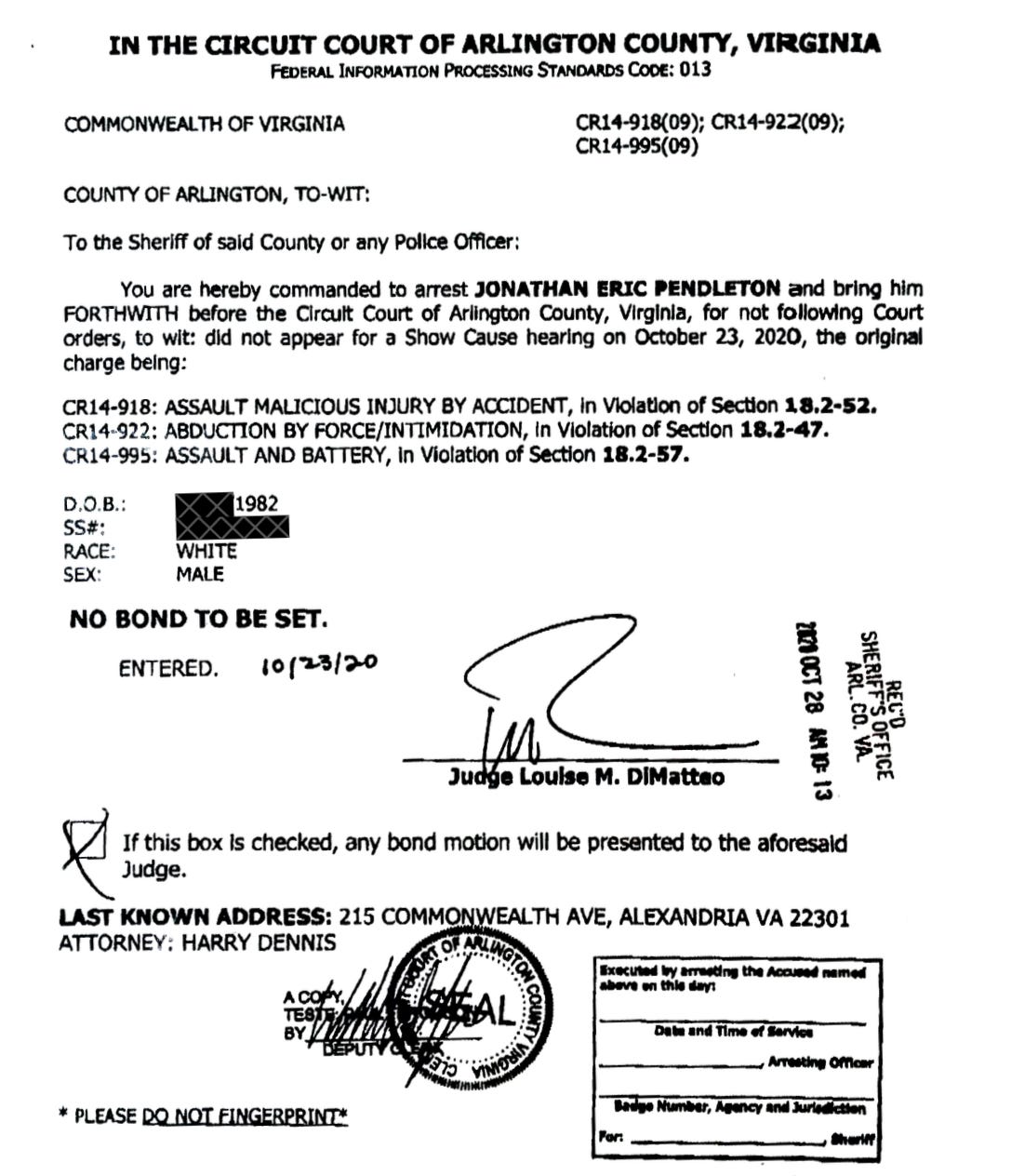

At this point, I decided to decline any further participation and a bench warrant was issued for “not following Court orders, to wit: did not appear for a Show Cause hearing on October 23, 2020” which was a “civil proceeding” pursuant to Va. Code § 19.2-182.7-8. However, the warrant, signed by Judge Louise DiMatteo, lists the “original charge[s]” she herself acquitted me of in 2014 — 1. MALICIOUS INJURY BY ACID, 2. ABDUCTION BY FORCE, and 3. ASSAULT AND BATTERY:

Facially, the warrant violates the Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment because “[f]or double jeopardy purposes, [a verdict of] not guilty by reason of insanity is a conclusion that criminal culpability had not been established, just as much as any other form of acquittal.” McElrath v. Georgia, 144 S. Ct. at 659, 601 U.S. 87, 217 L. Ed. 2d 419 (2024).

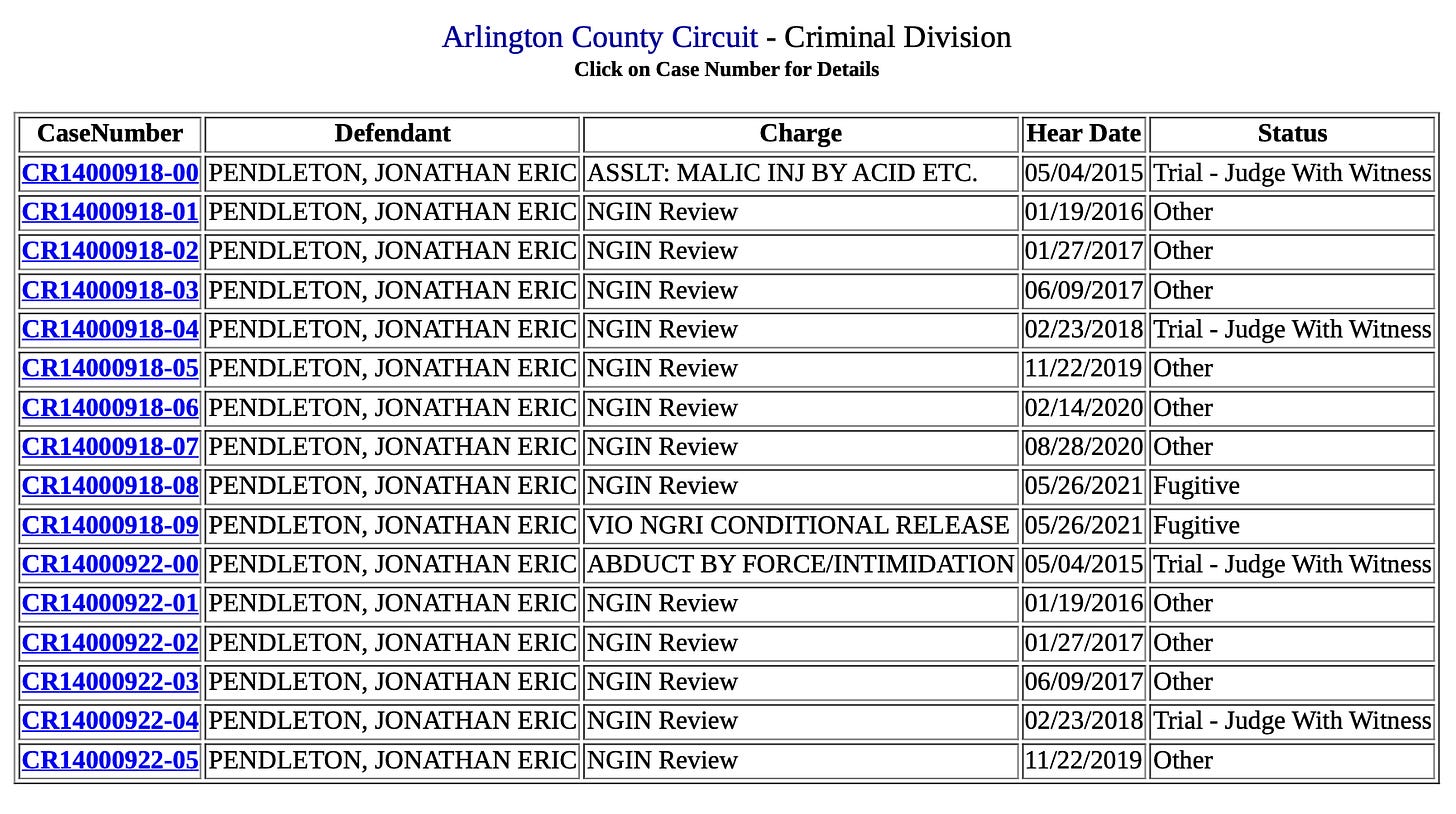

Nor is this a criminal matter. In spite of the fact that Virginia law superficially declares post-verdict NGRI hearings concerning insanity “acquittees” to be “civil proceedings,” Va. Code §§ 19.2-182.3, 5, 6, 8 — which is required by the Fourteenth Amendment after Foucha (“[acquittee] was not convicted, he may not be punished”), court clerks across the State continue to record all post-verdict hearings as criminal matters:

Thus, with the clerk recording civil proceedings as criminal, and the judge issuing a warrant that lists the “original charges,” the warrant appears to be for the crimes I was acquitted of in 2014, but is in reality — both as a matter of fact and law — nothing more than failure to appear for a civil hearing.

However, some months later, in February 2021, while living and working back in Seattle, I received a confusing letter from the State Department’s Bureau of Consular Affairs, notifying me that my passport had been revoked:

“This office was informed that on October 23, 2020, the Arlington Circuit Court in Arlington, Virginia, entered a felony warrant for your arrest. Warrant number CR14-91809 charges you with failure to appear for the underlying charge of assault and battery. Accordingly, the Department has denied your passport application and has revoked U.S. Passport number 658311107, and any other valid passports issued to you, pursuant to 22 C.F.R. §§ 51.60(b)(9).”

The number is a continuation of CR14000918, the felony charge for “MALICIOUS INJURY BY ACID” that I was acquitted of in 2014. Despite efforts throughout 2021, I was unable to conclusively determine what this Arlington bench warrant actually says.

In May of 2022, I had moved to Austin, Texas, and needed to renew my identification to obtain a security badge at work (as a Software Engineer at Apple) and was arrested by Texas authorities who also had the impression I was charged with the felonies I was acquitted of in 2014. This was the first time I was able to see the bench warrant from Arlington but was not provided with a copy. I was held in solitary confinement for 10 days and released when Virginia declined to extradite. It was at this point that I discovered that Virginia’s NGRI statutes had been unconstitutional for decades.

In August 2022, the first of many petitions for a writ of habeas corpus was filed in the Circuit Court of Arlington County (CL22003186, signed and notarized from Texas), challenging the entirety of my post-verdict detention in Virginia as facially unconstitutional:

“EQUAL PROTECTION: A verdict of NGRI ... is an acquittal in the sense that the defendant is absolved of criminal responsibility, the sentence intends no punitive disposal, and the matter is thereafter treated as a civil process of rehabilitation. The US Supreme Court has made it clear in Baxstrom v. Herold (1966) and Foucha v. Louisiana (1992) that defendants found NGRI in the United States are entitled to the same protections afforded individuals facing purely civil commitment proceedings under Virginia code § 37.2-800, consistent with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This makes the separate NGRI commitment and release process in Virginia plainly unconstitutional. This petitioner seeks an order from this court declaring my continued and prolonged detention unlawful and ordering my immediate release, since § 37.2-817.4 caps mandatory outpatient treatment at 180 days.”

The Clerk of the Circuit Court of Arlington County, Paul Ferguson, who was named as a respondent in the August 2022 petition, immediately began retaliating by refusing to complete service on any of the court’s orders, refusing to respond to FOIA requests for court records, and repeatedly delaying my employment background checks for up to a month. Ferguson did once personally return an acceptance of service when I filed a motion for default judgment — seemingly as a joke (petitioners can default but the court cannot). The Circuit Court of Arlington County issued a number of orders and judgments but I still don’t know what they say.

Sometime in late 2022 or early 2023, I reported this flagrant obstruction of justice committed by Mr. Ferguson’s office to the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, which should have put federal authorities on notice that the warrant and related State proceedings are not valid.

In March 2023, a second petition for a writ of habeas corpus was filed in the Supreme Court of Virginia, again challenging the State’s NGRI statutes as facially unconstitutional. The petition was eventually dismissed on June 29, 2023, after the respondents twice refused to accept service because, as the court was informed, I could not afford process service on the three respondents and the Attorney General’s office. This is very plainly a due process violation after Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371, 91 S. Ct. 780, 28 L. Ed. 2d 113 (1971) (indigent access rights).

Meanwhile, in April 2023, I had also filed a proposed class action suit for damages and declaratory relief in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia at Alexandria. See Pendleton v. Miyares, et al., E.D.Va. No. 1:23-CV-446. The complaint makes claims against Paul Ferguson for First Amendment access retaliation, and against Jason Miyares, Attorney General of Virginia, for failing to respond to the original habeas petition in Arlington. The preliminary statement says:

“Virginia has been on notice since at least 1977, when the first references to federal case law from [Baxstrom] appear in suits against state agents, that this NGRI procedure is constitutionally deficient on equal protection and due process grounds. See Evans v. Paderick, 443 F. Supp. 583 (E.D. Va. 1977). That this unconstitutional practice of ‘criminal commitment’ continues today in Virginia makes it appear intentionally punitive and cruel and ripe for class action.”

The complaint points out that Eighth Amendment jurisprudence has consistently held that it is cruel and unusual to punish people for having illnesses, e.g. Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660, 82 S. Ct. 1417, 8 L. Ed. 2d 758 (1962) (“It is unlikely that any State at this moment in history would attempt to make it a criminal offense for a person to be mentally ill, or a leper, or to be afflicted with a venereal disease. … Even one day in prison would be a cruel and unusual punishment for the ‘crime’ of having a common cold.”).

In May 2023, Paul Ferguson’s office, already being sued in federal court for retaliation, doubled down on further retaliation by reporting for the first time on my employment background checks that I am wanted for a nonexistent misdemeanor crime called “VIOLATION OF NOT GUILTY BY REASON OF INSANITY CONDITIONAL RELEASE,” causing my only professional job offer in 2023 (as a Network Engineer at Charter Communications) to be rescinded. There is no such crime in the State of Virginia.

The complaint in Alexandria was followed by the first attempt at federal habeas relief in July 2023 after the State’s dismissal, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254(b)(A-B). See Pendleton v. Miyares, et al., E.D.Va. No. 1:23-CV-446, ECF 8-10.

It was not until late summer 2023 that I was finally able to obtain a copy of the Arlington bench warrant from my court appointed attorney in Texas, and since the federal district court in Alexandria had at that point spent six months ignoring the pleadings, the warrant was first attached to the federal record in a petition for a writ of mandamus to the Fourth Circuit. See In re: Jonathan Pendleton, USCA4 No. 23-1987; also cross-filed in Pendleton v. Miyares, et al., E.D.Va. No. 1:23-cv-446, ECF 12, Exhibit A, (filed September 20, 2023).

On October 3rd, 2023, after ignoring the complaint for six months, Judge Leonie Brinkema dismissed the case exactly one day before the mandamus petition was scheduled to be answered. Id., ECF 13.

Rather than respond to the constitutional claims in the complaint and petition for habeas corpus, Judge Brinkema decided to charge me with a state crime herself, saying “[b]ecause Pendleton left Virginia while he was on conditional release and did not have permission from the court, he could be charged with a felony [escape under Va. Code § 19.2-182.15],” Id. at 3 (emphasis added), before later concluding that “plaintiff’s pleading reads as an attack on an ongoing state criminal prosecution — the arrest warrant for leaving the state while on conditional release.” Id. at 5 (emphasis added).

Judge Brinkema’s order of October 3rd, 2023, is the first time any mention of the felony escape statute, § 19.2-182.15, shows up in the record. None of the defendants had appeared or answered in any way, and no one was then alleging that I was charged with escape. Federal judges also lack jurisdiction over state crimes.

Moreover, the escape statute, § 19.2-182.15, violates the equal protection holding in Foucha because there is no analogous crime under the State’s civil commitment statutes. Virginia’s civil statute concerning “court review of mandatory outpatient treatment,” particularly “[i]f the person fails to appear for the hearing …,” does not include the word “felony.” Va. Code § 37.2-817.1(F). Similarly, Virginia’s civil statute concerning “any person who has been ordered to be involuntarily admitted to a facility escapes,” does not include the word “felony.” Va. Code § 37.2-833. There is simply no way to turn a civil commitment in Virginia into a felony prosecution.

Judge Brinkema’s allegation is akin to a federal judge accusing a black family bringing an action under the equal protection decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1955), or the due process decision in Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 74 S. Ct. 693, 98 L. Ed. 884 (1954), of committing the “crime” of trying to send their kids to “white” schools. Incredibly, Brinkema’s order says “[the complaint] does not meaningfully challenge any state law as violative of the Constitution.”

The order also makes derogatory comparisons to other complaints that have been dismissed as “frivolous” under 28 U.S.C. § 1915(e)(2)(B) such as King v. Rubenstein, 825 F.3d 206 (4th Cir. 2016) (removal of penis implants); Thomas v. The Salvation Army Southern Territory, 841 F.3d 632 (4th Cir. 2016) (woman alleging conspiracy to evict her from homeless shelters). But this section of the Prison Litigation Reform Act does not apply because I’m not a “prisoner.”

Judge Brinkema’s order further declares habeas corpus “inappropriate” and “moot” without explanation. Pendleton v. Miyares, et al., E.D.Va. No. 1:23-CV-446, ECF 13. Habeas corpus, which means something like “show that you have the body of law” that justifies any deprivation of liberty. It is a privilege of national citizenship under the U.S. Constitution, Art. I, § 9, cl. 2, which explicitly provides that “[t]he Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended.” Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723, 128 S. Ct. 2229, 171 L. Ed. 2d 41 (2008).

In short, Judge Brinkema’s order lacks any basis in fact or law and is a fraud upon the court designed to impede the administration of justice and deny an entire class of persons equal protection under the law.

And note the extraordinary coincidence that a State clerk in Arlington, Paul Ferguson, and a federal judge in Alexandria, Leonie Brinkema, are at this point doing exactly the same thing at the same time: denying access to the courts and claiming that I am charged with a crime.

According to CIA whistleblower John Kiriakou, Judge Brinkema “is known to reserve all national security cases for herself, rather than allow a rotation among the various Eastern District judges.” See “John Kiriakou: CIA’s Secret Torture Programs, MK‑Ultra, 9‑11, and Jailing Political Opponents.” The Tucker Carlson Network, June 2025.

A judicial misconduct complaint regarding Judge Brinkema’s behavior was sent to the Chief Judge of the Fourth Circuit, Albert Diaz, on October 11, 2023, and a similar complaint was sent to the Judicial Council of the Fourth Circuit in November, both of which were dismissed with boilerplate language saying the complaint “lacks sufficient evidence to raise an inference that misconduct has occurred.” 28 U.S.C. § 352(b)(1)(A)(iii).

Incredibly, what is clearly a premeditated crime under 18 U.S.C. § 242, a deprivation of rights under color of law of exactly the kind seen in Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 25 L. Ed. 676, 25 L. Ed. 2d 676 (1880) (judge jailed for denying equal protection), does not qualify as judicial misconduct.

Around this time, in late 2023, I complained to the Public Integrity Section of the DOJ that the Fourth Circuit had refused to enforce the canons of judicial conduct pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 351–364, and the response was that I was again subjected to warrantless wiretapping by the FBI and threatened with various criminal charges.

I first became aware of this after I received an email from UMGC, a school I had not attended or heard from in several years, letting me know that I had been selected for their FBI honors program, a course of study in criminal justice (my declared major was software development). A few days later I received an order for a book called “Managing Government Assets,” a collection of studies in public finance; curiously, my Amazon seller account that listed this book for sale had been deactivated years earlier. The FBI would go on to threaten me through various channels with disability fraud, filing false documents, tax evasion, and a variety of other obscure federal crimes.

Meanwhile, since Judge Brinkema had declared habeas corpus “moot,” a second petition was sent to the Richmond Division of the Eastern District of Virginia. Pendleton v. DiMatteo, et al., No. 3:23-CV-734 (filed Nov. 1st, 2023).

On November 30, 2023, Judge Roderick Young dismissed the petition with reference to Judge Brinkema’s order, calling me a criminal and saying saying “Pendleton has failed to exhaust available state remedies or demonstrate that exceptional circumstances warrant consideration.” Pendleton v. DiMatteo, et al., No. 3:23-CV-734. Judge Young’s order deliberately ignored the fact that the Supreme Court of Virginia had dismissed my petition for habeas corpus on June 29, 2023. The dismissal order was attached at Exhibit G. This is the only exhaustion requirement for federal habeas review. See Rose v. Lundy, 455 U.S. 509, 102 S. Ct. 1198, 71 L. Ed. 2d 379 (1982) (state’s highest court “had an opportunity to pass upon the matter”).6

Judge Young’s order is another fraud on the court designed to impede the administration of justice and deny an entire class of persons equal protection under the law. This has now become a pattern.

In December of 2023, Judge Young’s order was appealed to the Fourth Circuit pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2) in Pendleton v. DiMatteo, et al., USCA4 No. 23-7293. On January 8, 2024, finally compelled to respond to the multiple petitions for habeas corpus, Nelson Smith, Commissioner of DBHDS, represented by Jason Miyares, Attorney General of Virginia, and others in his office, repeated the same false allegations invented by Judge Brinkema in Alexandria months earlier, saying “a warrant was issued for [Pendleton’s] arrest for the felony offense of leaving Virginia while he was on conditional release, pursuant to Va. Code § 19.2-182.15.” Id., ECF 12 at 2. These State officials also repeated the very same falsehoods offered by Judge Young in Richmond, claiming “Pendleton did not exhaust his state court remedies,” and “is not being detained” but is rather a “fugitive.” Id. at 5-6.7

Ironically, Miyares was already being sued in the Alexandria case for failing to respond to the original habeas petition in the Circuit Court of Arlington County in 2022.

On March 22, 2024, I emailed Jessica Aber, then federal prosecutor for the Eastern District of Virginia, notifying her of “criminal acts committed by Jason S. Miyares, Attorney General of Virginia, and others in his office, in violation of 18 U.S.C. §§ 1001, 242. Please see the false statements regarding a warrant for my arrest and exhaustion of State remedies in USCA4 No. 23-7293, ECF 12, and my response in ECF 14.” The only reaction to this was that Miyares himself gained access to my devices and began harassing me in various ways on social media, threatening to bankrupt me, have me arrested, etc. When I was typing an appeal brief, someone assumed to be Miyares highlighted in a local PDF file the phrase “subject him to the hatred, ridicule, or contempt of his fellow men.” Warren, Samuel D., and Louis D. Brandeis. “The right to privacy.” Harv. L. Rev. 4 (1890): 193.

As this was happening, Judge Brinkema’s order dismissing the original lawsuit filed in Alexandria was being appealed separately in Pendleton v. Miyares, et al., No. 23-7039 (4th Cir. 2024). On February 21, 2024, a Fourth Circuit panel made up of judges Robert King, James Wynn, and William Traxler Jr., dismissed the appeal with a single sentence, referring to 28 U.S.C. § 1915 without explanation in an unpublished per curium opinion affirming all of several errors of material fact and law.

A petition for rehearing en banc was sent to the entire Fourth Circuit and denied on March 19th, 2024, meaning that Chief Judge Diaz and the unknown panel of judges on the Judicial Council who had already refused to respond to Judge Brinkema’s misconduct in the district court at Alexandria were made aware that the appellate panel of King, Wynn, and Traxler, had dismissed a constitutional challenge to State law that is indisputably correct, involving the fundamental liberty interests of an entire class of Virginians, without comment. And no circuit judge bothers to call a vote for rehearing.

On the evening of May 13, 2024, I mailed a box of twelve petitions for certiorari to the Supreme Court asking for review of the decisions originating from the Alexandria case in USCA4 No. 23-7039, and to assume jurisdiction over the pending habeas petition from Richmond, USCA4 No. 23-7293, in keeping with 28 U.S.C. § 2101(e), e.g. United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. at 692, 94 S. Ct. 3090, 41 L. Ed. 2d 1039 (1974), and issue an original writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2241(c)(3). See Pendleton v. Miyares, et al., No. 23-7500 (U.S. 2024).

At this point, the Fourth Circuit was still sitting on the separate habeas appeal from Richmond in No. 23-7293. Once I had a tracking number from the post office on the morning of May 14, 2024, I emailed the Attorney General’s office in Virginia to let them know the petition for certiorari was on the way, and within a couple hours the very same panel of Fourth Circuit judges, King, Wynn, and Traxler, dismissed the pending habeas appeal in Pendleton v. DiMatteo, et al., No. 23-7293 (4th Cir. 2024) (again ignoring the fact that Virginia’s highest court had dismissed my petition). The timing of the order indicates ex parte communication between Virginia officials and these Fourth Circuit judges and a preexisting agreement to dismiss.

What has been described thus far is undeniably evidence of a conspiracy against rights involving state and federal officials in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 241, including Paul Ferguson, Leonie Brinkema, Roderick Young, Jason Miyares, Robert King, James Wynn, William Traxler Jr., and Albert Diaz, among others. But the conspiracy is not limited to Virginia.

A Multidistrict Judicial Conspiracy

After Ferguson’s office in Arlington further retaliated by reporting on my employment background checks that I’m charged with a crime that does not exist, I filed suit under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), 15 U.S.C. § 1681, et seq., in the Western District of Texas at Austin. The amended complaint documents two specific instances where credit reporting agencies that had previously cleared me for employment were both newly reporting that I’m wanted for a crime that is simply not on the books, both times disputed and affirmed by the clerk’s office in Arlington — the only thing that had changed was that I had sued Ferguson in the Eastern District of Virginia.8

While Judge Brinkema had fabricated a felony charge of escape, Ferguson’s office was reporting that I am charged with a misdemeanor “VIOLATION OF NOT GUILTY BY REASON OF INSANITY CONDITIONAL RELEASE.” The reports are based on court records that refer to Va. Code § 19.2-182.7 but there is no such crime in Virginia. Having a conditional release revoked altogether is not a crime under Va. Code § 19.2-182.8 (“The hearing is a civil proceeding.”).

But the magistrate in Austin refers again to Judge Brinkema’s allegation in Alexandria even though this is irrelevant to the FCRA disclosures at issue, recommending that the case be dismissed as “frivolous” pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1915(e)(2)(B) and repeating the nonsense that clerks are immune from suit. Cf. Woodard v. Andrus, 419 F.3d 348 (5th Cir. 2005); Courthouse News Service v. Schaefer, 2 F.4th 318 (4th Cir. 2021); Pulliam v. Allen, 466 U.S. 522, 104 S. Ct. 1970, 80 L. Ed. 2d 565 (1984).

The magistrate also called the claims duplicative though the facts and legal bases were entirely unique, and posited that the defendant CRAs (HireRight) were just accurately reporting court records that could not be challenged. Cf. Henson v. CSC Credit Services, 29 F.3d 280 (7th Cir. 1994) (state court docket inaccurate).

Finally, quoting directly from Judge Brinkema’s order, the magistrate repeated the libel that caused the suit, calling me a criminal and a “fugitive from justice.” Doe v. CHARTER COMMUNICATIONS LLC, No. 1: 23-CV-01458 (W.D. Tex. 2023).

I wrote careful objections pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 636(b)(1)(C), explaining that “[the Virginia] matter is — in all legal respects — decidedly civil.” Remember, “[acquittee] was not convicted, he may not be punished.”

On January 22, 2024, Judge Robert Pittman dismissed the case with a single sentence: “Having done [a de novo review] and for the reasons given in the [magistrate’s] report and recommendation, the Court overrules Plaintiff’s objections and adopts the report and recommendation as its own order.” Doe v. CHARTER COMMUNICATIONS LLC, No. 1: 23-CV-01458 (W.D. Tex. 2024).

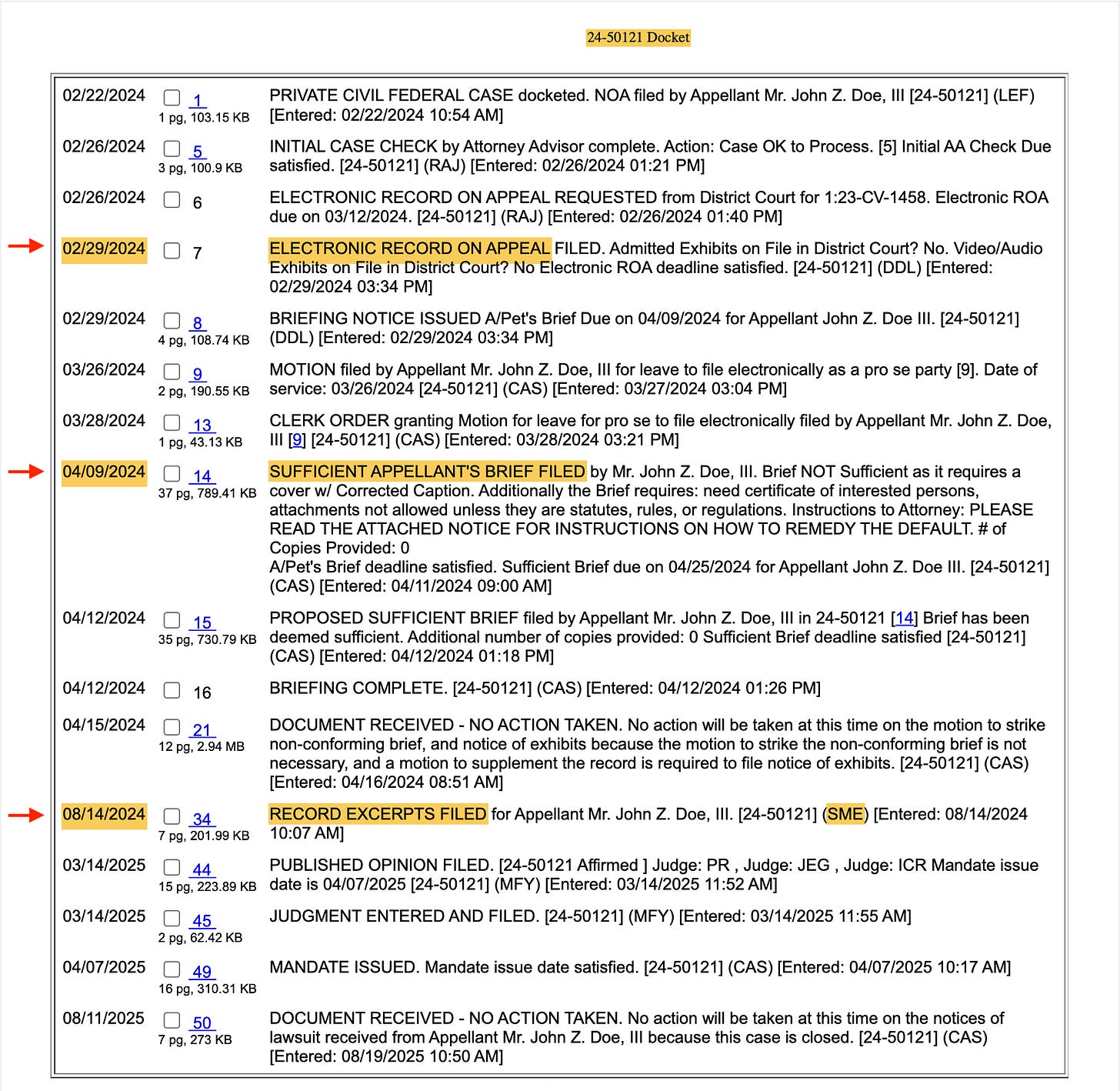

Judge Pittman knows this is not what a de novo review entails — the court’s reasoning should be stated without reference to any previous conclusions or assumptions. That’s what makes it “de novo.” See In re Garcia, 535 B.R. 721 (W.D. Tex. 2015). I wrote an appeal to the Fifth Circuit in April, basically just copying and pasting the objections the district court had failed to answer. See Doe v. CHARTER COMMUNICATIONS, LLC, 5CCA No. 24-50121.

And because it had become clear at this point that I was being intentionally denied access to the courts in Virginia and would likely remain professionally unemployable in the United States for the foreseeable future, I filed suit against the State Department in the Court of Federal Claims on April 22, 2024, seeking the return of my passport under the Just Compensation Clause of the Fifth Amendment. The complaint says that I am “not charged with a crime as a matter of fact, and could not be charged with a crime as a matter of law.” Pendleton v. United States, Fed. Cl. No. 1:24-CV-656.

In July 2024, without disputing the facts, the Government moved to dismiss for failure to state a claim because, essentially, “Mr. Pendleton has no property interest in his passport, which belongs solely to the United States Government.” Id., ECF 11.

In the summer of 2024, I was living temporarily in Washington, D.C., struggling to survive waiting tables, visiting old friends, and hoping to find legal representation in the city. The petition for certiorari was pending in the Supreme Court during the summer recess and the return of my passport did not seem promising given the recent filing from the DOJ. I was receiving threats of arrest on a daily basis from Jason Miyares, the Attorney General of Virginia, who was manipulating the background images in my browser tabs to display S.W.A.T. teams, sting operations, and boxing matches (Miyares’ antics are always childishly self-referential and easily identified). I’d also had several encounters in D.C. with persons assumed to be federal informants who seemed to be trying to get me to say something admissible about my income tax filing habits, or just outright threatening me. Out of concern that there might be a contrived arrest planned in the event the Supreme Court were to dismiss my petition, I decided to apply for political asylum in Canada.

In the evening of August 13, 2024, I made an irregular border crossing into Quebec by bicycle, through a cornfield outside Alburgh, Vermont. The next day, on August 14, someone in the Fifth Circuit clerk’s office using the initials SME reposted the order of the district court in Austin dismissing my FCRA suit with a single sentence. See Doe v. CHARTER COMMUNICATIONS, LLC, 5CCA No. 24-50121, ECF 34.

It is important to understand the sequence of events to see how bizarre this excerpt from SME really is. Here is the Fifth Circuit docket highlighting (1) that the record on appeal was filed in February, (2) that my brief citing the record was filed in April, and (3) that on August 14, 2024, the day I entered Canada, someone called SME reposts the district court’s fraudulent order:

There is no legitimate reason the district court’s order would be reposted to the Fifth Circuit docket since it was already part of the record on appeal filed six months earlier. This was obviously intended as a threat to dismiss the appeal in a similar fashion (without review), and, just like the ex parte communication between the Office of the Attorney General in Virginia and the Fourth Circuit panel, the timing of the message from SME is part of the message. SME in the Fifth Circuit clerks office in New Orleans apparently has the same surveillance capability that Cowen, Miyares, and the FBI have.

On August 26th, 2024, I applied for asylum in Canada as a person in need of protection from persecution under the U.N. treaty of 1951, citing government sanctioned retaliation that has permanently impaired my livelihood, persistent threats of trumped-up charges from state and federal officials, and a risk of cruel and unusual punishment upon return.

The Supreme Court denied my petition for certiorari on October 7, 2024, which was not unexpected since the petition deals mostly with the misapplication of existing law and the record in the lower courts was entirely undeveloped.9

A few weeks later, on October 24, I mailed a Petition For Rehearing pursuant to S. Ct. Rule 44.2 because I had discovered previously unidentified Brady violations in the record surrounding Professor Cowen’s perjured testimony that were never raised and would tend to undermine confidence in the 2014 verdict, e.g. Smith v. Cain, 565 U.S. 73, 132 S. Ct. 627, 181 L. Ed. 2d 571 (2012) (key witness might have been impeached). I also thought the Court might be interested to know that the retaliation from state and federal officials for having filed civil rights lawsuits against Virginia had made it impossible for me to live in the United States, at least in part because of Professor Cowen’s ties to CIA-funded surveillance company Palantir. That petition was denied first thing Monday morning, but is available online, without need of a PACER account, as part of the historical record on the Supreme Court’s website.

On October 29, 2024, the Court of Federal Claims dismissed the suit concerning my passport, agreeing with the Government that citizens have no compensable property interest in their passports (which is incorrect but not indefensible).

The court also found that the State Department had “determine[d] or [was] informed by competent authority” that “on October 23, 2020, the Arlington Circuit Court in Arlington, Virginia entered a felony warrant for [Plaintiff’s] arrest,” referring to the felonies I was acquitted of in 2014.

Simultaneously, referring once again to Judge Brinkema’s allegations in Alexandria, Judge Zach Sommers decided that I “could” or “shall be” guilty of yet another felony for escape under Va. Code § 19.2-182.15, and because these facts are not subject to dispute it would not be in the interest of justice to transfer the case to the district court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1631. See Pendleton v. United States, Fed. Cl. No. 1:24-CV-656. These are rather suspicious findings of fact, to put it mildly.

In February, 2025, I wrote the U.S. Congress to report that I was continuing to receive threats from what I presume are Government adjacent entities — threats to continue to deny me access to the courts, threats to empty my bank account, threats to charge me under the Espionage Act, and threats to have me assassinated like President John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., John McAfee, and, most recently, Alexei Navalny. I also reported this activity to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, who are now monitoring the situation.

In March 2025, the Fifth Circuit made good on the threat from SME and affirmed the dismissal of my FCRA complaint in Austin, which the court implied was “fantastic or delusional.” Doe v. CHARTER COMMUNICATIONS, LLC, 131 F.4th 323 (5th Cir. 2025). The panel of judges, Priscilla Richman, James Graves Jr., and Irma Carillo Ramirez, used more words than Judge Pittman in the district court, but came no closer to the substance of the appeal.

The panel says the “claim against Ferguson in this case and the Virginia case both involve the same series of events and contain allegations of many of the same facts” and is “duplicative and therefore frivolous,” Id. (internal quotes omitted), whereas “stated in Appellant’s objections, these claims are entirely unique to this suit and involve specific disclosures that occurred months after the suit in the Eastern District of Virginia’s Alexandria Division was filed — in fact, these disclosures are being made by Defendant Ferguson’s office as ongoing retaliation for having filed that suit.” Id., ECF 14-1 at 13.

The panel then merely repeats the magistrate’s argument that “records from the Arlington County Circuit Court indicate that the warrant was a criminal matter. … [and] we are unable to conclude that HireRight’s report did not accurately report the information contained in those records.” Id. But this “was the crux of USDA v. Kirtz … where the Supreme Court held that furnishers of information provided to CRAs are also responsible for accuracy even when they are government officials, i.e. ‘any person.’” Id., ECF 14-1 at 23-24.

Fifth Circuit judges James Graves Jr., Irma Carillo Ramirez, and Priscilla Richman have thus willfully refused to engage with the arguments in good faith which suggests ex parte communication with SME and a preexisting agreement to dismiss the case.

As I was reading the Fifth Circuit decision the following day, March 15, 2025, I was reminded of the recently ousted president of Harvard, Claudine Gay, and went to the Wikipedia page to refresh my memory of the episode, saying to myself, “how fake does it get before you’re asked to resign?” — at which point the Fifth Circuit resent its decision via email, as if the court recognized something of itself in the story.

At this point, any casual observer reading the record would conclude that the United States does not have an independent or impartial judiciary; the system is rigged no matter the district or circuit; the courts have an agenda and are targeting specific litigants.

If there are any lingering doubts about my legal analysis with respect to the cases involving Virginia, I am also unable to get a fair hearing in a Seattle employment discrimination suit having nothing to do with state or federal government. See Pendleton v. REVATURE LLC, et al, No. 2: 22-cv-01399-TL (W.D. Wash. 2022). Counsel for the defendants was recently caught falsifying testimonial evidence and transparently lied to the court about it — the kind of misconduct that should get them disbarred. Both Rules 26(g)(3) and 37(a)(5) of the FRCP strictly require sanctions for improper attorney certifications and failure to deliver verified interrogatories, but Judge Tana Lin somehow blamed the defendants’ fraud on me, the plaintiff, and then ordered defense counsel to perjure their clients — effectively assisting them in defrauding the court. Id., ECF 79-84, 92. This was then affirmed by the Chief Judge of the Western District of Washington and by the Ninth Circuit. The courts are fake, in other words.

Current Posture

The FBI is reporting that I am charged with felonies I was acquitted of in 2014;

Arlington is reporting a nonexistent misdemeanor crime on my background checks;

Multiple state and federal officials have claimed that I am charged with yet another felony that I have not in fact been properly charged with and which violates the equal protection holding in Foucha.

Virginia has been avoiding compliance with the Supreme Court’s holdings in Foucha for more than thirty years and as a consequence has falsely imprisoned me for more than ten years; I have been rendered professionally unemployable in retaliation for filing civil rights lawsuits; I have been denied access to the courts, both state and federal, habeas corpus has been suspended, and I still have not found legal representation in either the U.S. or Canada. There has been no hearing and no merits based decision on any constitutional claims.

On April 4, 2025, I mailed another complaint seeking the return of my passport to the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, once again re-alleging I am “not charged with a crime as a matter of fact, and could not be charged with a crime as a matter of law.” Pendleton v. United States, et al, No. 1:25-CV-01218 (D.C. 2025). The clerk’s office tried to prevent me from filing this suit, which they posted to the docket only after being reported to the FBI, and the court has so far done its best to ignore the pleadings.

On April 10, 2025, as the case was being filed, the Government responded to a Freedom of Information Act request identifying the alleged victim in the underlying case, Professor Tyler Cowen and his associates, Alex Tabarrok and Mark Thornton — both of whom were mentioned in my 2014 testimony, as federal “personnel” under 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(6). See id., Dkt. 12-1, Ex. A. This is what the courts have been trying to cover up:

This FOIA document makes Cowen’s 2014 testimony in the Circuit Court of Arlington County about his relationship to Tabarrok and Thornton thoroughly impeachable, e.g. Banks v. Dretke, 540 U.S. 668, 124 S. Ct. 1256, 157 L. Ed. 2d 1166 (2004) (witness discredited for failure to disclose exculpatory evidence). Together with Cowen’s personal ties and business dealings with Palantir co-founder Peter Thiel, who manages a company that offers exactly the same cyberstalking capabilities I was describing in 2014, and which was also suppressed at trial, the amended complaint filed in August asserts that these facts constitute proof that I am actually innocent of both “insanity” and the original charges.

The amended complaint further makes claims against ten federal judges who have violated the Ku Klux Klan Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1985 -- conspiring to cover up not just the cruel and unusual punishment of American citizens but also the pervasive surveillance activities of the U.S. Government.10

Under current judicial immunity standards, judges are liable for actions taken in “clear absence of all jurisdiction,” Bradley v. Fisher, 80 U.S. 335, 20 L. Ed. 646, 20 S. Ct. 646 (1872), and federal judges clearly have no jurisdiction over state crimes.

Unfortunately, after these past few years of lawfare, I have every reason to believe that the defamations complained of, that I am “criminally insane,” have reached other countries and are now beyond the control of any court. Because of its proximity to the United States, it is unlikely that there is a “durable solution” available in Canada that would allow me to return to professional work. I will therefore need to create an entirely new identity somewhere else — a process that will likely take years, just to have the chance to start my life over again.

Thus, the deprivation of liberty is “not merely freedom from bodily restraint but also the right of the individual to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized . . . as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.” Board of Regents of State Colleges v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564, 92 S. Ct. 2701, 33 L. Ed. 2d 548 (1972).

As I explained to the Supreme Court, there is, unfortunately, a certain antipathy towards the insanity defense in many states, which don’t like this area of law and have avoided complying with Foucha, and the federal government (to include a decidedly non-indenpendent judiciary) is wary of lending credibility to this case because of the background information cited here. Even though the lawsuits have until recently been solely about State law in Virginia, the federal courts seem to have been aware the entire time that the alleged victim in the underlying case, Professor Tyler Cowen, is part of the national surveillance system and have been desperate to cover this up.

In other words, the federal judiciary does not care that I’m innocent, or that an entire class of people across the country are being abused: they don’t want anyone to notice that we live in a surveillance state that is sadistically targeting its own citizens.

Please share this story and consider making a contribution to my legal defense fund: https://www.givesendgo.com/defeat-big-brother

Note that the timestamps currently displayed in the archives at marginalrevolution.com are inaccurate; the originals were exhibited as evidence at trial in the Circuit Court of Arlington County, Virginia, in 2014.

This is textbook common law, still in full force in many states. “A private person may arrest another ... [w]hen the person arrested has committed a felony, although not in his presence ... [or] [w]hen a felony has been in fact committed, and he has reasonable cause for believing the person arrested to have committed it.” Black’s Law Dictionary. Black, Henry Campbell, 1990.

During closing arguments, my public defender argued that a simple assault had occurred over the Internet and that this “breach of the peace” justified my arrest of Cowen. Yet simple assault requires physical proximity and is therefore impossible over the Internet. See Harper v. Com., 196 Va. 723, 85 S.E.2d 249, 85 S.E. 249 (1955).

See Idaho Code § 18-207(a) (1987) (”Mental condition shall not be a defense to any charge of criminal conduct.”).

See Greenberg, Andy and Mac, Ryan. “How A ‘Deviant’ Philosopher Built Palantir, A CIA-Funded Data-Mining Juggernaut.” Forbes. August 14, 2013.

Judge Young also invents a theory that an invalid arrest warrant does not constitute “custody” for habeas purposes, which lacks any basis in law. See Jones v. Cunningham, 371 U.S. 236, 83 S. Ct. 373, 9 L. Ed. 2d 285 (1963) (“precedent can leave no doubt that, besides physical imprisonment, there are other restraints on a man’s liberty, restraints not shared by the public generally, which have been thought sufficient in the English-speaking world to support the issuance of habeas corpus.”).

The term “fugitive” connotes criminality: “A person who, having committed a crime, flees .…” Black, H.C., 1968. Black’s Law Dictionary, Revised Fourth Edition (p. 800).

The amended complaint also asserts a substantive due process right to privacy of the kind found in Whalen v. Roe, 429 U.S. 589, 97 S. Ct. 869, 51 L. Ed. 2d 64 (1977) (J. Brennan, concurring), owing to disclosures of sensitive medical information.

SUP. CT. R. 10 (“A petition for a writ of certiorari is rarely granted when the asserted error consists of erroneous factual findings or the misapplication of a properly stated rule of law.”)

It’s quite clear that the 1871 Congress intended a “bad faith” or “actual malice” standard for damage claims against judicial officers who “knowingly or recklessly” violate the Constitution. See unsigned note, “JUDICIAL IMMUNITY AT THE (SECOND) FOUNDING: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON § 1983.” Harvard Law Review, Vol. 136 (2022).